What are signs that a volcano is going to erupt

How tin can we tell when a volcano will erupt and how practise we set up for an eruption?

a GPS campaign

Students behave a GPS campaign to measure basis deformation on the flank of Kilauea, Hawaii, 2013.

Volcanic eruptions are almost always preceded by days, weeks, months, or years of alert activity which reflects the movement or pressurization of magma, peculiarly at volcanoes that take not erupted in centuries or longer (like all of Canada'southward volcanoes). These signs of unrest include earthquakes (which may be detectable just with seismographs), basis deformation (which may be detectable only with surveying equipment, GPS instruments, or satellite imagery), gas emissions, and heat anomalies, also as gravity, magnetic, and geoelectrical phenomena. These phenomena are readily detectable, and can thus be used in volcano monitoring – the systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of data before, during, and after eruptions, for the purpose of making short-term (days to weeks) forecasts of eruptions or changes in eruptions. The ability to monitor volcanoes effectively is crucial to reducing risks from volcanic hazards.

A seismic monitoring station

Newly-installed seismic monitoring station near Nazko cone, British Columbia, 2007.

There are many recent examples of eruptions where volcano monitoring data were used to successfully forecast an eruption. The forecast of the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo (the second largest eruption in the twentieth century) is an first-class instance: information technology has been estimated that tens of thousands of lives were saved due to evacuations. Removal of property (specially vehicles and aircraft) from areas effectually the volcano also saved at least 250 million U.S. dollars, and these savings far outweighed the costs of monitoring. The Mount Pinatubo eruption is a specially noteworthy instance of successful forecasting because the volcano was non monitored prior to the unrest that was first observed iii months earlier the cataclysmic eruption. Volcano monitoring conducted during times when no unrest is occurring is useful because it establishes a baseline for the volcano'due south behaviour, nonetheless, even where at that place is fiddling or no pre-unrest monitoring, short-term forecasting may exist successful, every bit was the instance at Pinatubo.

Every volcano is different, and the processes that dictate whether an eruption will occur, how big it will be, what hazards will exist present, and what areas will exist afflicted, are complex. Sometimes a volcano will experience low-level unrest that lasts for weeks or months but does not culminate in eruption (as was the case during the Nazko region seismic swarm in central British Columbia in 2007). At other times, days, weeks, or months of escalating unrest volition be followed by an eruption (as was the example at Mount St. Helens in 1980). Sometimes a volcano will continue to erupt at brusk intervals for many years (as has been the example with the Soufrière Hills volcano on Montserrat, which has been erupting since 1995). Sometimes a volcano will experience escalating unrest that ceases without eruption; such situations can be especially problematic because the making of an unfulfilled eruption forecast (a "false warning") can cause scientists to lose credibility. Volcano monitoring is nevertheless a new and evolving science, and there is always some uncertainty in a forecast, both because of the limits of available cognition and the inherent uncertainty in natural systems.

Nazko gas monitoring

Scientists measuring soil gas content near Nazko cone, British Columbia in 2007.

In Canada, there is no ongoing monitoring at private volcanoes because eruptions are so infrequent. Withal, Natural Resource Canada'due south Canadian National Seismograph Network (CNSN) currently monitors volcanic regions in British Columbia and the Yukon and can detect very small earthquakes. If unrest were detected nigh a Canadian volcano, NRCan would reply past providing boosted targeted monitoring of seismic action, footing deformation, gas emissions, and other phenomena in order to find out what was happening, and would prepare hazard maps and work closely with emergency planning agencies to ensure that authentic hazard information was available. During the 2007 Nazko seismic swarm in central British Columbia, which lasted two months and did non lead to an eruption, NRCan installed additional seismic stations, took soil gas measurements to expect for volcanic gas emissions, conducted field reconnaissance, and prepared a preliminary hazard map.

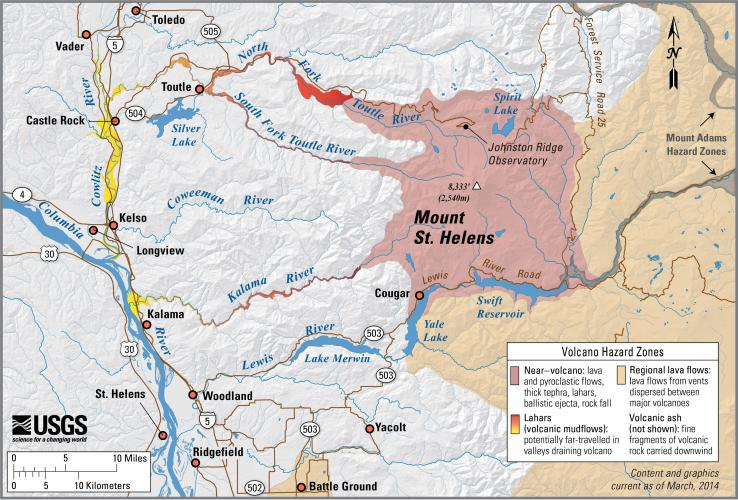

Mount St. Helens take a chance map

U.s.a. Geological Survey simplified risk map for Mountain St. Helens, Washington, showing the potential bear on areas for basis-based hazards during a volcanic eruption. Areas that might be affected by volcanic ash are non shown.

Volcano monitoring looks at the twenty-four hour period to day behaviour of a volcano. In contrast, geologic mapping and other studies at dormant volcanoes (conducted when unrest is not occurring) can assistance establish the past behaviour of a volcano, the frequency of eruption, the sizes of past eruptions, and the areas affected past by eruptions. The best key to what a volcano will do in the hereafter is what information technology has done in the past. Computer modelling can also help predict areas that will be afflicted by events (such as lava flows, pyroclastic flows, and lahars) of different sizes in the future. All of this data tin exist used to generate long-term forecasts of volcano behaviour (forecasts on a fourth dimension scale of decades to centuries or more) and to assist in hazard assessments and gamble mapping. For example, if Volcano X has erupted ten times during the last m years, we would say that information technology has a 100 twelvemonth return menstruation, and that the average almanac probability of an eruption is 1 in 100. This long-term forecast of 1 eruption every hundred years does not tell us what yr an eruption will occur, or that because an eruption has not occurred for 100 years that an eruption adjacent yr is guaranteed – but it does tell us that an eruption is more statistically probable at Volcano X than at a volcano that has only erupted one time in the concluding g years. Adventure maps and assessments, and long-term forecasts, can be very useful for emergency planning and for prioritizing volcano research and monitoring resources. Hazard assessment, hazard mapping, and volcano monitoring are all important in reducing the risk from volcanic hazards

Source: https://chis.nrcan.gc.ca/volcano-volcan/how-comment-en.php

0 Response to "What are signs that a volcano is going to erupt"

Post a Comment